I have to admit, listening to Chris Potter’s new album, “The Sirens,” is something of a surreal experience for me. The spacious and flowing songs conjured here by the Columbia native and saxophone colossus have been giving me a sense of being transported in time, something like Déjà vu.

I have to admit, listening to Chris Potter’s new album, “The Sirens,” is something of a surreal experience for me. The spacious and flowing songs conjured here by the Columbia native and saxophone colossus have been giving me a sense of being transported in time, something like Déjà vu.

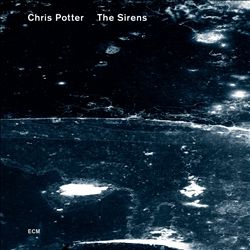

Now let me be clear, this languid, mind-expanding mood is not being solely induced by the atmospheric and exploratory jazz that’s being played. (Chill, it’s not what you’re thinking. Chemicals were not involved.) Part of it can be attributed to the fact that “The Sirens” is Potter’s first album for ECM Records, a label known for putting the avant in avant-garde jazz. In other words, the stuff on this label is out there. (ECM was founded in Munich, Germany, in 1969 by a double-bass player named Manfred Eicher, so you get the picture.)

But I’m getting ahead of myself. To better explain my depiction of ECM records, I need to go back to the 1970s when I was trying to expand my musical tastes by dipping into jazz. I discovered people like Larry Coryell, The Crusaders, and Grover Washington Jr. Then I traced their roots back to Wes Montgomery, Miles Davis, and Charlie Parker. In the middle of all this jazz teeth-cutting, I happened across an album by a pianist named Keith Jarrett that turned out to be the most non-conformist record I’d ever heard.

The first thing that struck me was the stark but-alluring artistic packaging. Very sophisticated, I thought. Secondly, the quality of the vinyl was a notch above other albums I owned. Most importantly, the music played by Jarrett and his trio was mind-expanding, hard-to-categorize stuff. I checked the label, saw that it was ECM, and went in search of more music from this eclectic company.

I discovered artists such as saxophonist Jan Garbarek, bassist Eberhard Weber, and guitarist Pat Metheny. Time and again, I was rewarded with music that was as challenging as it was beautiful.

In recent years, I’ve become reacquainted with ECM records and been blown away by releases from trumpeter Tomasz Stanko, The Tord Gustavson Trio, and pianist Nik Bartsch. Now comes the ECM debut from Chris Potter, Dreher High School grad and veteran of many jazz sessions as a teenager at Pug’s in Five Points. Granted, Potter, who's 42, has appeared on ECM records before, giving marvelous support to artists such as Dave Holland, Steve Swallow, and most notably, the late drummer Paul Motian, with whom Potter played on the stellar 2010 live album, “Lost in a Dream.”

But seeing his name displayed prominently on one of those cool ECM CD covers gave me chills. I’ve long considered Potter to be Columbia’s most important musical export ever, and this CD goes a long way in confirming that. Potter has almost 20 albums under his belt as a bandleader, including the masterful “Traveling Mercies” on Verve Records in 2002. But his entry into the ECM fraternity is especially gratifying, given the high standards for boldness and quality the label has set through the years. I could use words like sublime, transcending, and illuminating to describe Potter’s playing on “The Sirens,” but you really have to hear it for yourself. If you’re a jazz fan, check this record out. If you’re thinking about dipping into jazz, give this Columbia native son a try.

--- Mike Miller

(Editors note: For more of Mike Miller on Chris Potter, check out the forthcoming book, The Limelight (Muddy Ford Press, 2013) which releases on February 24th with a launch party at Tapp's from 5 - 8 pm)