Antoinette Nwandu’s Pass Over, inspired by Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, originally premiered in 2017. The production, turned into a film by Spike Lee, follows two black men in a liminal space, both outside of time and stuck within it. It is a play where everything and nothing happens, that both absorbs your projections onto it and drapes you in its meaning.

NiA Theatre Company’s production of Pass Over opened last weekend and aptly utilizes the space of the University of South Carolina’s black box at the Booker T. Washington building. Known as the Lab Theatre, the intimate space adds to the claustrophobia of the play. The set design, done by Cedric Umoja-Day, provides a backdrop that roots the characters to the unnamed city they’re stuck in. The newspaper headlines read as if from another time, but the scraps of cloth and scattered belongings create an image of an alley that could be around the corner today. Spatially, it becomes a tether that constantly pulls the actors back in, contributing to the lack of freedom physically and thematically.

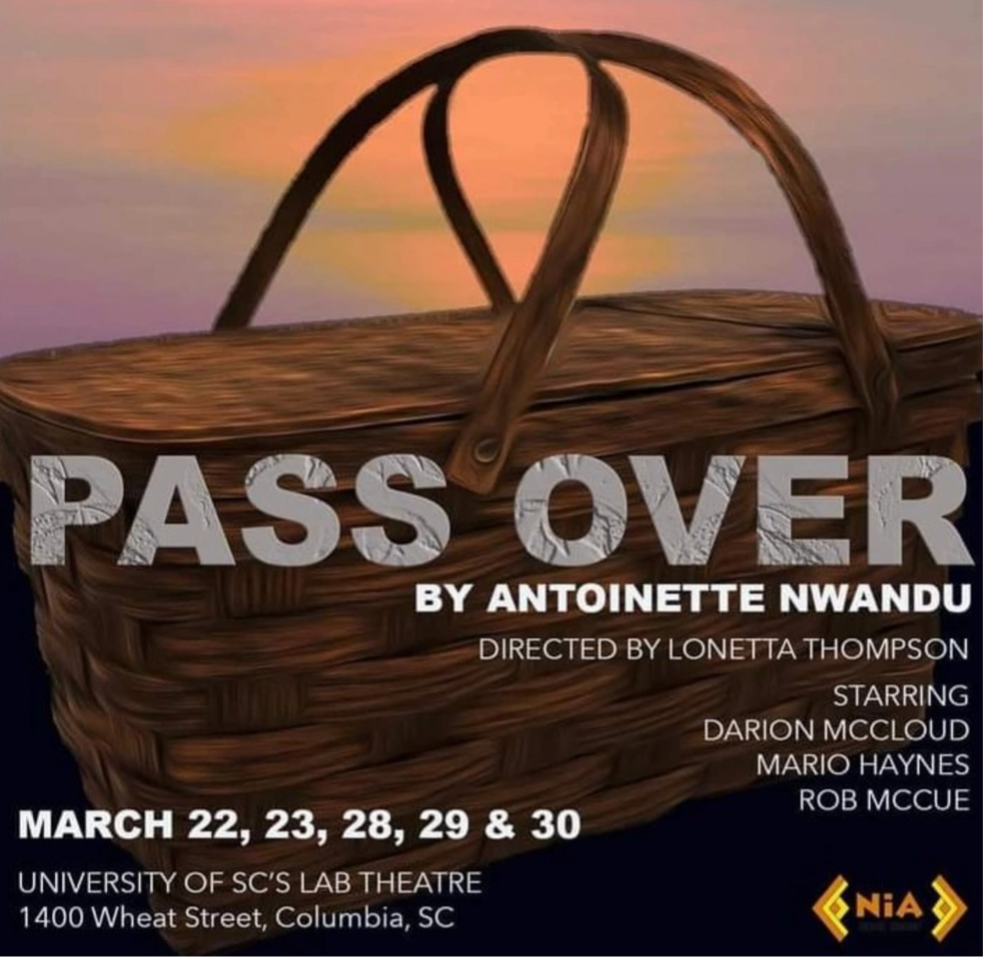

The costume designing by Taylor Thompson (who also did props) amplifies this. Moses and Kitch’s looks are understated and allow their performances to shine. Kitch’s outfit appears fairly contemporary and could be from any year in the past few decades, while Moses’ could be from anytime in the past century. The outfit on Rob McCue’s Mister, as well as his picnic basket, emphasizes him as a man of a different time, which adds to the audience’s unease even when he is not speaking.

What most keenly emphasizes the tense nature of the play, however, is the tremendous acting by the small cast of three. McCue as Mister is able to serve nuance in his eerie toxic positivity that walks the line between genuine and malicious. His police officer (“Ossifer”) is everything it should be – awful and manipulative. Mario Haynes as Kitch is funny, innocent, naïve – and yet his coming of age is served in moments of quiet that steal your breath. He is fully in control of actions loud and soft. He is, in short, the heart of the play. The leading role here, Moses, played by Darion McCloud (who also served as the Assistant Director), is the standout of the production. He is simply magnetic, electric, and it is hard to take your eyes off him. His joy, his anger, his confidence, his fear, his power, his loss – it is all palpable. He is the driving force of the show. There is no doubt this is anyone but Moses: this is all he has ever been, all he will be, and this is enough, even when it isn’t.

All these decisions, nuanced and loud alike, are led by Lonetta Thompson as director; at the helm, she steers this ship expertly. Having her cast move across the space, sitting even in the alcoves and stairs adjacent to the audience pulls the audience into it, collapsing boundaries and expanding the liminality’s borders. We cannot refuse our participation, our culpability. The decision to keep the play farcical with constant movement and exaggerated actions helps contrast with the emotional aspects of the play, making the moments of shock and loss sit even heavier.

This is a story where archetype and individuality are always in contest, and crafting it takes time and care, which is seen throughout. There were a couple stumbles, though minor. The lighting (led by Teddy Palmer) was great, used evenly in the first half and used to focus on certain characters as well as denote the passage of time in the second. At times, though, especially in the second half, the lighting shifts in a way that could be paralleling the breakdown of the play’s structure, but does not have quite enough intentionality to be clear. The sound design (led by Madeline Lewis) was solid, but all sounds were at a similar level. The faraway gunshots and the on-scene gunshots sounded identical, and the speech was louder than the gunshots. These are very minute slips in a fantastic production that rarely takes the audience out of the story.

In the end, this is a play where simplicity is everything, and working to amplify what is there without complicating it is a fine line. This team walks this line expertly, an act that cannot be so tidy without a stellar stage manager, a role filled by Colleen Kelly. Pass Over has an excellent book, but this particular production steeps you in it, making these two black men’s entrapment haunt patrons long after they leave the theatre.

If Columbia patrons can see it this final weekend before it leaves, they should. Tickets are available online.