I’ve been thinking about things lately. That is, I’ve been thinking about things. Material objects, physical things. How do things mean?

In part I’ve been thinking about things because of the grotesque consumerism of Black Friday, the greed of the season, and the ways that our culture encourages us to think love and happiness can be approximated and revealed in material objects. (Jewelry commercials seem especially icky examples of this.)

But I’ve also been thinking of things because of two installation art exhibits I saw during the December Jingle & Mingle on Main Street art crawl: Susan Lenz’s “Hung by the Chimney with Care” at S&S Art Supply and Amanda Ladymon’s “Kindred Harvest” at Frame of Mind.

Installation art is tricky. So much depends not on the idea, nor the execution, but on the things used. Socks, buttons, old cigar boxes, a Parcheesi board, yarn—things with little value, but weighted, in these projects, with meanings extraneous to the objects but integral to our perception of the art. A useful word for this for me is aura, not necessarily in the sense that Walter Benjamin uses it to talk about the almost religious authenticity we feel (or once felt, he insists, before photography destroyed it all) for a work of art. (And let me say here that I’m not an art theorist or an expert on Benjamin, just someone who likes to think about how artworks affect me, and why.) In both of these installations, the objects had to be more than what they were, and our response depended on the associations those things held in our perceptions, our reactions.

Ladymon’s work depends on our emotional associations with childhood board games and family photos, even those not our own: a couple on a beach, a little girl on a bike, a family portrait, a wedding, an ultrasound fetal image. I was moved by this display, but must admit that I wondered if there might be a fundamental disconnect in my experience of this work about familial, geographic, cultural connections, since these connections were marked not only by the overlay of photos over maps and images but also by the web of yarn connecting or not connecting these images to the Parcheesi board. I’ve never played Parcheesi. Although I have my own emotional and cultural associations with board games, and though I understand her explanation of how our lives and our families are created through unpredictable sequences of events, I sensed I might inevitably be missing something important about this work, since its heart was a resistant object, a thing that I didn’t understand.

Lenz, more perversely, demanded our attention to detritus, leftovers, garbage. In a piece she produced earlier this year, "Two Hours at the Beach," Lenz incorporated all the garbage she found in two hours on Folly Beach into an art quilt, making an ecological statement as well as a fascinating textile piece. (The quilt is currently part of a window display at Tapps.) If that earlier work raised litter to the level of art, Lenz amps up that process with the new installation, layering cultural and emotional meanings (including the kitsch, the cliché, emotional garbage) onto our experience of what is basically, a bunch of junk.

An artshop window filled with old socks, scattered buttons, and a sad artificial Christmas tree with shabby tinsel would be a perverse display, were it not for the explanation prominent in the window: that these things came from the laundry of the old state mental hospital, and that her impulse—foregrounded in the title, a line from that bit of sentimental Christmas kitsch, “The Night Before Christmas”—was to emphasize the idea that not everyone gets to celebrate Christmas with family, either because they can’t be there, or because they’re not welcome there. Junk here is transformed by our knowledge of its origins, like the beach trash but with a lot more cultural and political baggage. Not just the mental hospital but also the cultural fictions of family that demand kitsch-ified versions of the holiday that don’t match the experiences of many. Even our possibility for sympathy was registered in cliché—“There but by the grace of God go I,” a statement Lenz rendered on images of the hospital in cut-up letters like a ransom note.

But there were those socks, all those socks. Parodies of the clichéd hung stockings. Anonymous, leftover, but also registers of the authentic, the individual. If this installation was filled with junk, it reminded me of the ways our culture treats certain people as junk: the mentally ill who are forced onto the streets by budget cuts, those whose lives don’t fit the cheery fictions of the season—the divorced, the orphaned, the rejected.

The window was so weird and powerful for me, filled with junk and cliché but so insistent that the viewer find a capacity for empathy—so insistent on an emotional authenticity in the aura of those things. And so much depended on the origin of those things. (Would the window make sense without that explanation in the window?)

I say all this not to diminish these projects. I loved both, spent time with both, took my partner by to see both when he made it down after doing time eating over-salted food at some office party at a Vista sports bar.

What we do with things, how we think about things, the aura of things—this is part of how art works.

I have an artwork in my office at home: a page ripped from an old book, the poem “Sad Mementoes,” the first words of which are “Bereaved and forlorn.” Other words are difficult to make out, since the page has been distressed with electric tape. It’s an object marked by the process of erasure: lighter color, roughened texture, where the paper’s foxing and the poem’s ink have been lifted off the page with tape. Above the title there is an image of a statue from a photo proofsheet. Affixed to the page with a remnant of that black tape is pressed botanical specimen.

The work of Barry Jones, MFA student at USC back in the mid-1990s when I first came to the university, it is, for me, a haunting piece. I don’t have to know that it is about his brother, or mental illness, or a book he found at a local antique shop for it to make sense, though those associations are now part of what it is and how it means.

Put a bone in a box—I’m thinking of my tenth-grade exhibit of animal skulls found on the farm—and it’s an object. Call it “Reliquary,” and suddenly bones and boxes are weighted with a different kind of meaning—emotions, intimations of mortality. They mean at a different register, not because of the objects but because of the aura of associations we have now for those objects.

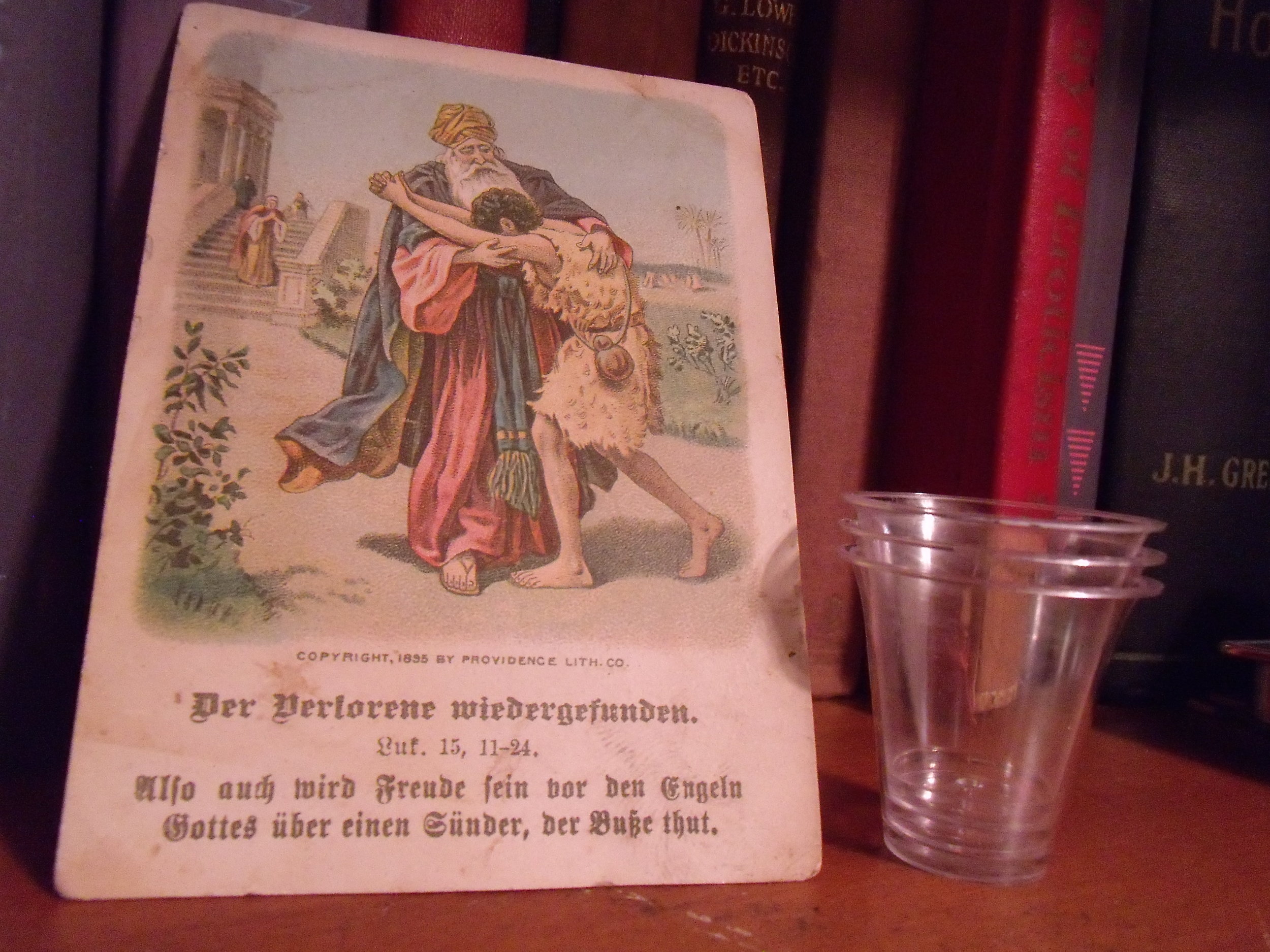

As I type this, I’m wearing my father’s grey and black plaid flannel shirt, its literal warmth surely augmented by the emotion I associate with its wearing. He passed away earlier this year. He didn’t speak to me for almost a decade, literally, after I came out as a gay man, and I didn’t go home for Christmas for the past 16 years. I spent three months earlier this year helping with his hospice care. On my bookshelf there are three tiny plastic cups. Clutter to anyone else, litter to another, but to me, a memory: one of those times that folks from church brought by the ritual bread and wine (crackers and grape juice), and we drank from those cups, me, my mother, and my father, lying in his hospital bed.

year. He didn’t speak to me for almost a decade, literally, after I came out as a gay man, and I didn’t go home for Christmas for the past 16 years. I spent three months earlier this year helping with his hospice care. On my bookshelf there are three tiny plastic cups. Clutter to anyone else, litter to another, but to me, a memory: one of those times that folks from church brought by the ritual bread and wine (crackers and grape juice), and we drank from those cups, me, my mother, and my father, lying in his hospital bed.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about things. What we do with things. How they mean.

-- Ed Madden